Email: a.vanniekerk@pgr.reading.ac.uk

Mountains come in many shapes and sizes and as a result their dynamic impact on the atmospheric circulation spans a continuous range of physical and temporal scales. For example, large-scale orographic features, such as the Himalayas and the Rockies, deflect the atmospheric flow and, as a result of the Earth’s rotation, generate waves downstream that can remain fixed in space for long periods of time. These are known as stationary waves (see Nigam and DeWeaver (2002) for overview). They have an impact not only on the regional hydro-climate but also on the location and strength of the mid-latitude westerlies. On smaller physical scales, orography can generate gravity waves that act to transport momentum from the surface to the upper parts of the atmosphere (see Teixeira 2014), playing a role in the mixing of chemical species within the stratosphere.

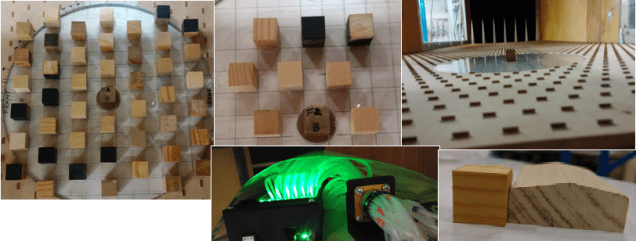

Figure 1 shows an example of the resolved orography at different horizontal resolutions over the Himalayas. The representation of orography within models is complicated by the fact that, unlike other parameterized processes, such as clouds and convection, that are typically totally unresolved by the model, its effects are partly resolved by the dynamics of the model and the rest is accounted for by parameterization schemes.However, many parameters within these schemes are not well constrained by observations, if at all. The World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) Working Group on Numerical Experimentation (WGNE) performed an inter-model comparison focusing on the treatment of unresolved drag processes within models (Zadra et al. 2013). They found that while modelling groups generally had the same total amount of drag from various different processes, their partitioning was vastly different, as a result of the uncertainty in their formulation.

Climate models with typically low horizontal resolutions, resolve less of the Earth’s orography and are therefore more dependent on parameterization schemes. They also have large model biases in their climatological circulations when compared with observations, as well as exhibiting a similarly large spread about these biases. What is more, their projected circulation response to climate change is highly uncertain. It is therefore worth investigating the processes that contribute towards the spread in their climatological circulations and circulation response to climate change. The representation of orographic processes seem vital for the accurate simulation of the atmospheric circulation and yet, as discussed above, we find that there is a lot of uncertainty in their treatment within models that may be contributing to model uncertainty. These uncertainties in the orographic treatment come from two main sources:

- Model Resolution: Models with different horizontal resolutions will have different resolved orography.

- Parameterization Formulation: Orographic drag parameterization formulation varies between models.

The issue of model resolution was investigated in our recent study, van Niekerk et al. (2016). We showed that, in the Met Office Unified Model (MetUM) at climate model resolutions, the decrease in parameterized orographic drag that occurs with increasing horizontal resolution was not balanced by an increase in resolved orographic drag. The inability of the model to maintain an equivalent total (resolved plus parameterized) orographic drag across resolutions resulted in an increase in systematic model biases at lower resolutions identifiable over short timescales. This shows not only that the modelled circulation is non-robust to changes in resolution but also that the parameterization scheme is not performing in the same way as the resolved orography. We have highlighted the impact of parameterized and resolved orographic drag on model fidelity and demonstrated that there is still a lot of uncertainty in the way we treat unresolved orography within models. This further motivates the need to constrain the theory and parameters within orographic drag parameterization schemes.

References

Nigam, S., and E. DeWeaver, 2002: Stationary Waves (Orographic and Thermally Forced). Academic Press, Elsevier Science, London, 2121–2137 pp., doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-382225-3. 00381-9.

Teixeira MAC, 2014: The physics of orographic gravity wave drag. Front. Phys. 2:43. doi:10.3389/fphy.2014.00043 http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fphy.2014.00043/full

Zadra, A., and Coauthors, 2013: WGNE Drag Project. URL:http://collaboration.cmc.ec.gc.ca/science/rpn/drag_project/

van Niekerk, A., T. G. Shepherd, S. B. Vosper, and S. Webster, 2016: Sensitivity of resolved and parametrized surface drag to changes in resolution and parametrization. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc., 142 (699), 2300–2313, doi:10.1002/qj.2821.