Charlie Suitters – c.c.suitters@pgr.reading.ac.uk

The Beast from the East, the record-breaking winter warmth of February 2020, the Canadian heat dome of 2022…what do these three events have in common? Well, many things I’m sure, but most relevantly for this blog post is that they all coincided with the same phenomenon – atmospheric blocking.

So what exactly is a block? An atmospheric block is a persistent, large-scale, quasi-stationary high-pressure system sometimes found in the mid-latitudes. The prolonged subsidence associated with the high pressure suppresses cloud formation, therefore blocks are often associated with clear, sunny skies, calm winds, and temperature extremes. Their impacts can be diverse, including both extreme heat and extreme cold, drought, poor air quality, and increased energy demand (Kautz et al., 2022).

Despite the range of hazards that blocking can bring, we still do not fully understand the dynamics that cause a block to start, maintain itself, and decay (Woollings et al., 2018). In reality, many different mechanisms are at play, but the importance of each process can vary between location, season, and individual block events (Miller and Wang, 2022). One process that is known to be important is the interaction between blocks and smaller synoptic-scale transient eddies (Shutts, 1983; Yamazaki and Itoh, 2013). By studying a 43-year climatology of atmospheric blocks and their anticyclonic eddies (both defined by regions of anomalously high 500 hPa geopotential height), I have found that on average, longer blocks absorb more synoptic anticyclones, which “tops up their anticyclonicness” and allows them to persist longer (Fig. 1).

It’s great that we now know this relationship, however it would be beneficial to know if these interactions are forecasted well. If they are not, it might explain our shortcomings in predicting the longevity of a block event (Ferranti et al., 2015). I explore this with a case study from March 2021 using ensemble forecasts from MOGREPS-G. Fortunately, this block in March 2021 was not associated with any severe weather, but it was still not forecasted well. In Figure 2, I show normalised errors in the strength, size, and location of the block, at the time of block onset, for each ensemble member from a range of different initialisation times. In these plots, a negative (positive) value means that the block was forecast to be too weak (strong) or too small (large), and the larger the error in the location, the further away the forecast block was from reality. In general, the onset of this block was forecast to be to be too weak and too small, though there was considerable spread within the ensemble (Fig. 2). Certainty in the forecast was only achieved at relatively small lead times.

Now for the interesting bit – what causes the uncertainty in forecasting of the onset this European blocking event? To examine this, I grouped forecast members from an initialisation time of 8 March 2021 according to their ability to replicate the real block: the entire MOGREPS-G mean, members that either have no block or a very small block (Group G), members that perform best (Group H), and members that predict area well, but have the block in the wrong location (Group I). Then, I take the mean geopotential height anomalies ( ) at each time step in each group, and compare these fields between groups to see if I can find a source of forecast error.

) at each time step in each group, and compare these fields between groups to see if I can find a source of forecast error.

This is shown as an animation in Fig. 3. The animation starts at the time of block onset, and goes back in time to selected validity times, as shown at the top of the figure. The domain of the plot also changes in each frame, gradually moving westwards across the Atlantic. By looking at the ERA5 (the “real”) evolution of the block, we see that the onset of the European block was the result of an anticyclonic transient eddy breaking off from an upstream blocking event over North America. However, none of the aforementioned groups of members accurately simulate this vortex shedding from the North American block. In most cases, the eddy leaving the North American block is either too weak or non-existent (as shown by the blue shading, representing that the forecast  is much weaker than in ERA5), which resulted in a lack of Eastern Atlantic blocking altogether. Only the group that modelled the block well (Group H) had a sizeable eddy breaking off from the upstream block, but even in this case it was too weak (paler blue shading). Therefore, the uncertain block onset in this case is directly related to the way in which an anticyclonic eddy was forecast to travel (or not) across the Atlantic, from a pre-existing block upstream. This is interesting because the North American block itself was modelled well, yet the eddy that broke off it was not, which was vital for the onset of the Euro-Atlantic block.

is much weaker than in ERA5), which resulted in a lack of Eastern Atlantic blocking altogether. Only the group that modelled the block well (Group H) had a sizeable eddy breaking off from the upstream block, but even in this case it was too weak (paler blue shading). Therefore, the uncertain block onset in this case is directly related to the way in which an anticyclonic eddy was forecast to travel (or not) across the Atlantic, from a pre-existing block upstream. This is interesting because the North American block itself was modelled well, yet the eddy that broke off it was not, which was vital for the onset of the Euro-Atlantic block.

To conclude, this is an important finding because it shows the need to accurately model synoptic-scale features in the medium range in order to accurately predict blocking. If these eddies are absent in a forecast, a block might not even form (as I have shown), and therefore potentially hazardous weather conditions would not be forecast until much shorter lead times. My work shows the role of anticyclonic eddies towards the persistence and forecasting of blocks, which until now had not be considered in detail.

References

Kautz, L., Martius, O., Pfahl, S., Pinto, J.G., Ramos, A.M., Sousa, P.M., and Woollings, T., 2022. “Atmospheric blocking and weather extremes over the Euro-Atlantic sector–a review.” Weather and climate dynamics, 3(1), pp305-336.

Miller, D.E. and Wang, Z., 2022. Northern Hemisphere winter blocking: differing onset mechanisms across regions. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 79(5), pp.1291-1309.

Shutts, G.J., 1983. The propagation of eddies in diffluent jetstreams: Eddy vorticity forcing of ‘blocking’ flow fields. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 109(462), pp.737-761.

Suitters, C.C., Martínez-Alvarado, O., Hodges, K.I., Schiemann, R.K. and Ackerley, D., 2023. Transient anticyclonic eddies and their relationship to atmospheric block persistence. Weather and Climate Dynamics, 4(3), pp.683-700.

Woollings, T., Barriopedro, D., Methven, J., Son, S.W., Martius, O., Harvey, B., Sillmann, J., Lupo, A.R. and Seneviratne, S., 2018. Blocking and its response to climate change. Current climate change reports, 4, pp.287-300.

Yamazaki, A. and Itoh, H., 2013. Vortex–vortex interactions for the maintenance of blocking. Part I: The selective absorption mechanism and a case study. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 70(3), pp.725-742.

A true revolutionary in the field of theoretical physics and abstract algebra, Amelie Emmy Noether was a German-born inspiration thanks to her perseverance and passion for research. Instead of teaching French and English to schoolgirls, Emmy pursued the study of mathematics at the University of Erlangen. She then taught under a man’s name and without pay because she was a women. During her exploration of the mathematics behind Einstein’s general relativity alongside renowned scientists like Hilbert and Klein, she discovered the fundamentals of conserved quantities such as energy and momentum under symmetric invariance of their respective quantities: time and homogeneity of space. She built the bridge between conservation and symmetry in nature, and although Noether’s Theorem is fundamental to our understanding of nature’s conservation laws, Emmy has received undeservedly small recognition throughout the last century.

A true revolutionary in the field of theoretical physics and abstract algebra, Amelie Emmy Noether was a German-born inspiration thanks to her perseverance and passion for research. Instead of teaching French and English to schoolgirls, Emmy pursued the study of mathematics at the University of Erlangen. She then taught under a man’s name and without pay because she was a women. During her exploration of the mathematics behind Einstein’s general relativity alongside renowned scientists like Hilbert and Klein, she discovered the fundamentals of conserved quantities such as energy and momentum under symmetric invariance of their respective quantities: time and homogeneity of space. She built the bridge between conservation and symmetry in nature, and although Noether’s Theorem is fundamental to our understanding of nature’s conservation laws, Emmy has received undeservedly small recognition throughout the last century. Claudine Hermann is a French physicist and Emeritus Professor at the École Polytechnique in Paris. Her work, on physics of solids (mainly on photo-emission of polarized electrons and near-field optics), led to her becoming the first female professor at this prestigious school. Aside from her work in Physics, Claudine studied and wrote about female scientists’ situation in Europe and the influence of both parents’ works on their daughter’s professional choices. Claudine wishes to give girls “other examples than the unreachable Marie Curie”. She is the founder of the Women and Sciences association and represented it at the European Commission to promote gender equality in Science and to help women accessing scientific knowledge. Claudine is also the president of the European Platform of Women Scientists which represents hundreds of associations and more than 12,000 female scientists.

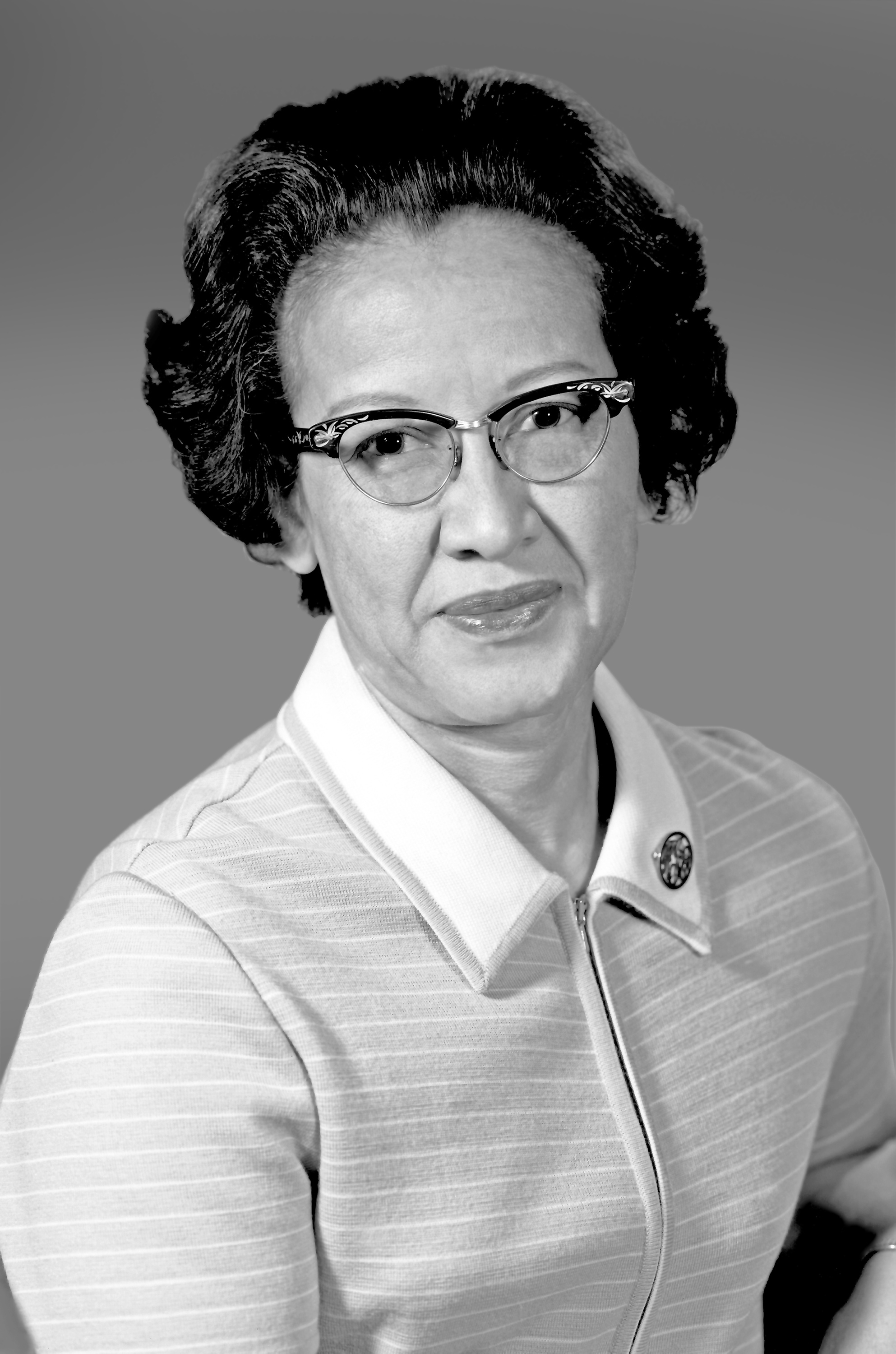

Claudine Hermann is a French physicist and Emeritus Professor at the École Polytechnique in Paris. Her work, on physics of solids (mainly on photo-emission of polarized electrons and near-field optics), led to her becoming the first female professor at this prestigious school. Aside from her work in Physics, Claudine studied and wrote about female scientists’ situation in Europe and the influence of both parents’ works on their daughter’s professional choices. Claudine wishes to give girls “other examples than the unreachable Marie Curie”. She is the founder of the Women and Sciences association and represented it at the European Commission to promote gender equality in Science and to help women accessing scientific knowledge. Claudine is also the president of the European Platform of Women Scientists which represents hundreds of associations and more than 12,000 female scientists. For most people being handpicked to be one of three students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools would probably be the most notable life achievements. However for Katherine Johnson’s this was just the start of a remarkable list of accomplishments. In 1952 Johnson joined the all-black West Area Computing section at NACA (to become NASA in 1958). Acting as a computer, Johnson analysed flight test data, provided maths for engineering lectures and worked on the trajectory for America’s first human space flight.

For most people being handpicked to be one of three students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools would probably be the most notable life achievements. However for Katherine Johnson’s this was just the start of a remarkable list of accomplishments. In 1952 Johnson joined the all-black West Area Computing section at NACA (to become NASA in 1958). Acting as a computer, Johnson analysed flight test data, provided maths for engineering lectures and worked on the trajectory for America’s first human space flight.

Women however were not allowed on such ships, thus Marie Tharp was stationed in the lab, checking and plotting the data. Her drawings showed the presence of the North Atlantic Ridge, with a deep V-shaped notch that ran the length of the mountain range, indicating the presence of a rift valley, where magma emerges to form new crust. At this time the theory of plate tectonics was seen as ridiculous. Her supervisor initially dismissed her results as ‘girl talk’ and forced her to redo them. The same results were found. Her work led to the acceptance of the theory of plate tectonics and continental drift.

Women however were not allowed on such ships, thus Marie Tharp was stationed in the lab, checking and plotting the data. Her drawings showed the presence of the North Atlantic Ridge, with a deep V-shaped notch that ran the length of the mountain range, indicating the presence of a rift valley, where magma emerges to form new crust. At this time the theory of plate tectonics was seen as ridiculous. Her supervisor initially dismissed her results as ‘girl talk’ and forced her to redo them. The same results were found. Her work led to the acceptance of the theory of plate tectonics and continental drift. Ada Lovelace was a 19th century Mathematician popularly referred to as the “first computer programmer”. She was the translator of “Sketch of the Analytical Engine, with Notes from the Translator”, (said “notes” tripling the length of the document and comprising its most striking insights) one of the documents critical to the development of modern computer programming. She was one of the few people to understand and even fewer who were able to develop for the machine. That she had such incredible insight into a machine which didn’t even exist yet, but which would go on to become so ubiquitous is amazing!

Ada Lovelace was a 19th century Mathematician popularly referred to as the “first computer programmer”. She was the translator of “Sketch of the Analytical Engine, with Notes from the Translator”, (said “notes” tripling the length of the document and comprising its most striking insights) one of the documents critical to the development of modern computer programming. She was one of the few people to understand and even fewer who were able to develop for the machine. That she had such incredible insight into a machine which didn’t even exist yet, but which would go on to become so ubiquitous is amazing!

Over the past months, researchers in the

Over the past months, researchers in the