Over the past ~decade, extended-range forecasts of river flow have begun to emerge around the globe, combining meteorological forecasts with hydrological models to provide seasonal hydro-meteorological outlooks. Seasonal forecasts of river flow could be useful in providing early indications of potential floods and droughts; information that could be of benefit for disaster risk reduction, resilience and humanitarian aid, alongside applications in agriculture and water resource management.

While seasonal river flow forecasting systems exist for some regions around the world, such as the U.S., Australia, Africa and Europe, the forecasts are not always accessible, and forecasts in other regions and at the global scale are few and far between. In order to gain a global overview of the upcoming hydrological situation, other information tends to be used – for example historical probabilities based on past conditions, or seasonal forecasts of precipitation. However, precipitation forecasts may not be the best indicator of floodiness, as the link between precipitation and floodiness is non-linear. A recent paper by Coughlan-de-Perez et al (2017), “should seasonal rainfall forecasts be used for flood preparedness?”, states:

“Ultimately, the most informative forecasts of flood hazard at the seasonal scale are streamflow forecasts using hydrological models calibrated for individual river basins. While this is more computationally and resource intensive, better forecasts of seasonal flood risk could be of immense use to the disaster preparedness community.”

Over the past months, researchers in the Water@Reading* research group have been working with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), to set up a new global scale hydro-meteorological seasonal forecasting system. Last week, on 10th November 2017, the new forecasting system was officially launched as an addition to the Global Flood Awareness System (GloFAS). GloFAS is co-developed by ECMWF and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC), as part of the Copernicus Emergency Management Services, and provides flood forecasts for the entire globe up to 30 days in advance. Now, GloFAS also provides seasonal river flow outlooks for the global river network, out to 4 months ahead – meaning that for the first time, operational seasonal river flow forecasts exist at the global scale – providing globally consistent forecasts, and forecasts for countries and regions where no other forecasts are available.

Over the past months, researchers in the Water@Reading* research group have been working with the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), to set up a new global scale hydro-meteorological seasonal forecasting system. Last week, on 10th November 2017, the new forecasting system was officially launched as an addition to the Global Flood Awareness System (GloFAS). GloFAS is co-developed by ECMWF and the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC), as part of the Copernicus Emergency Management Services, and provides flood forecasts for the entire globe up to 30 days in advance. Now, GloFAS also provides seasonal river flow outlooks for the global river network, out to 4 months ahead – meaning that for the first time, operational seasonal river flow forecasts exist at the global scale – providing globally consistent forecasts, and forecasts for countries and regions where no other forecasts are available.

The new seasonal outlook is produced by forcing the Lisflood hydrological river routing model with surface and sub-surface runoff from SEAS5, the latest version of ECMWF’s seasonal forecasting system, (also launched last week), which consists of 51 ensemble members at ~35km horizontal resolution. Lisflood simulates the groundwater and routing processes, producing a probabilistic forecast of river flow at 0.1o horizontal resolution (~10km, the resolution of Lisflood) out to four months, initialised using the latest ERA-5 model reanalysis.

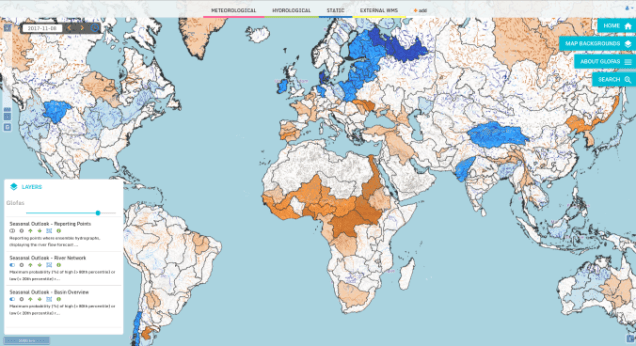

The seasonal outlook is displayed as three new layers in the GloFAS web interface, which is publicly (and freely) available at www.globalfloods.eu. The first of these gives a global overview of the maximum probability of unusually high or low river flow (defined as flow exceeding the 80th or falling below the 20th percentile of the model climatology), during the 4-month forecast horizon, in each of the 306 major world river basins used in GloFAS-Seasonal.

The second layer provides further sub-basin-scale detail, by displaying the global river network (all pixels with an upstream area >1500km2), again coloured according to the maximum probability of unusually high or low river flow during the 4-month forecast horizon. In the third layer, reporting points with global coverage are displayed, where more forecast information is available. At these points, an ensemble hydrograph is provided showing the 4-month forecast of river flow, with thresholds for comparison of the forecast to typical or extreme conditions based on the model climatology. Also displayed is a persistence diagram showing the weekly probability of exceedance for the current and previous three forecasts.

Over the coming months, an evaluation of the system will be completed – for now, users are advised to evaluate the forecasts for their particular application. We welcome any feedback on the forecast visualisations and skill – feel free to contact me at the email address below!

To find out more, you can see the University’s press release here, further information on SEAS5 here, and the user information on the seasonal outlook GloFAS layers here.

*Water@Reading is “a vibrant cross-faculty centre of research excellence at the University of Reading, delivering world class knowledge in water science, policy and societal impacts for the UK and internationally.”

Full list of collaborators:

Rebecca Emerton1,2, Ervin Zsoter1,2, Louise Arnal1,2, Prof. Hannah Cloke1, Dr. Liz Stephens1, Dr. Florian Pappenberger2, Prof. Christel Prudhomme2, Dr Peter Salamon3, Davide Muraro3, Gabriele Mantovani3

1 University of Reading

2 ECMWF

3 European Commission JRC

Contact: r.e.emerton@pgr.reading.ac.uk

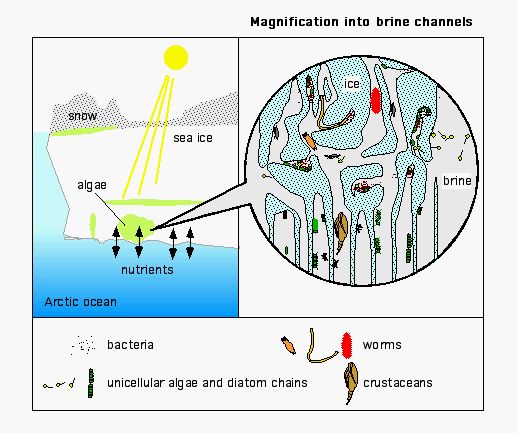

Schematic showing some dynamic features of sea ice 3.

Schematic showing some dynamic features of sea ice 3.