Thea Stevens – thea.stevens@pgr.reading.ac.uk

Juan Garcia Valencia – j.p.garciavalencia@pgr.reading.ac.uk

Introduction

Hi there! We are Thea (3rd year PhD) and Juan (2nd year PhD), and we had the privilege to attend Week 2 of COP29 at the end of last year. We thought it would be a good idea to write a blog as an accumulation of answers to the main questions we’ve encountered since coming back – we hope you enjoy reading about it and that it’s hopefully useful to anyone thinking of applying for this amazing opportunity next year!

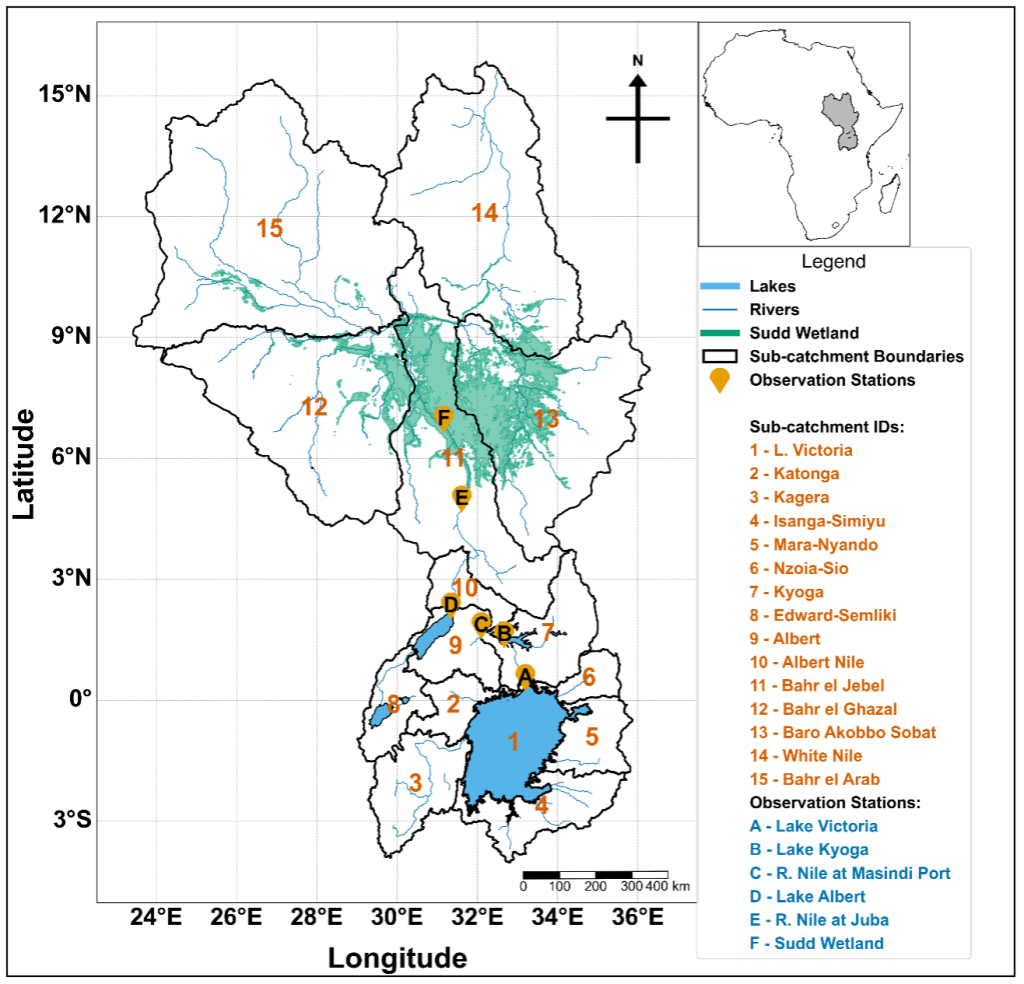

Picture 1, Entrance to COP29. Picture 2, Emmanuel Essah, Thea Stevens and Juan Garcia Valencia in COP29

Pre-COP

What is COP29?

COP29, the 29th Conference of the Parties, is the annual United Nations climate change conference and serves as the primary decision-making event under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Established by the treaty signed in 1992, COP brings together representatives from all UN member states and the European Union to address global climate challenges. This year, COP29 was held in November in Baku, Azerbaijan, drawing over 65,000 delegates from around the world, including diplomats, climate scientists, trade union leaders, and environmental activists. The event aims to negotiate effective strategies to combat the root causes of climate change. In essence, it’s the world’s largest and most significant gathering dedicated to climate action.

What were the expectations going into COP29?

Even before the summit began, COP29 was widely referred to as the “Finance COP” due to the prominence of one particular issue: climate finance. This term highlights the obligation of developed nations to provide financial resources to developing countries. These funds are intended to help nations build clean-energy systems, adapt to a warming world, and recover from disasters exacerbated by climate change. A significant focus of the negotiations and media coverage was the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), a proposed climate finance target aimed at channelling resources to developing nations to combat climate change effectively.

However, discussions were also expected to extend beyond finance, addressing crucial topics such as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, as well as strategies for adaptation and mitigation. We had the incredible opportunity to attend the second week of COP29—a pivotal stage of the process when ministers usually tackle the intricate details of agreements crafted in the first week, working to reach consensus. Heading into the conference, we anticipated hearing much more about the NCQG and its potential connections to other pressing climate issues.

Why did we apply to go?

“I decided to apply to attend COP29 due to the significance of geopolitical progress in ensuring that countries act in accordance with science. I think it is easy for us to forget the magnitude of what we study as meteorologists and climate scientists. To be able to follow how our scientific understanding shapes what actions are taken on a political scale feels important in order to put our work into context. I have also been following the progress of COPs for a long time – I was that geeky teenager in geography class who got a bit obsessed with the developments made there. So, on a more personal level, it also felt like a really exciting opportunity.” – Thea

“My decision to apply for COP29 stemmed from a deep interest in the science-policy interface. As a PhD student researching monsoons and their variability with climate change, my work primarily involves analysing large datasets with the aim of crafting papers that can inform decision-making. While this scientific foundation is critical, I was eager to move beyond the confines of my computer screen and engage directly with the global climate community. This experience promised not only professional growth but also the chance to see firsthand how research and advocacy converge on the global stage so I knew I had to give it a go!” – Juan

What did we do in preparation?

Having closely followed previous COPs and participated in COPCAS, we were familiar with the structure and nature of these conferences, which gave us a sense of what to expect. However, we knew that attending in person would be a completely different experience. In preparation, we undertook extensive training and courses. The Walker Institute’s help was invaluable, as they provided numerous opportunities to upskill and address our questions. They even arranged security training, given that we were heading to a politically sensitive region. Additionally, the IISD webinars were incredibly helpful in providing up-to-date insights on negotiation progress and key facts. Staying informed through these resources and keeping up with current news allowed us to approach the conference well-prepared and confident.

During COP

What was the schedule like?

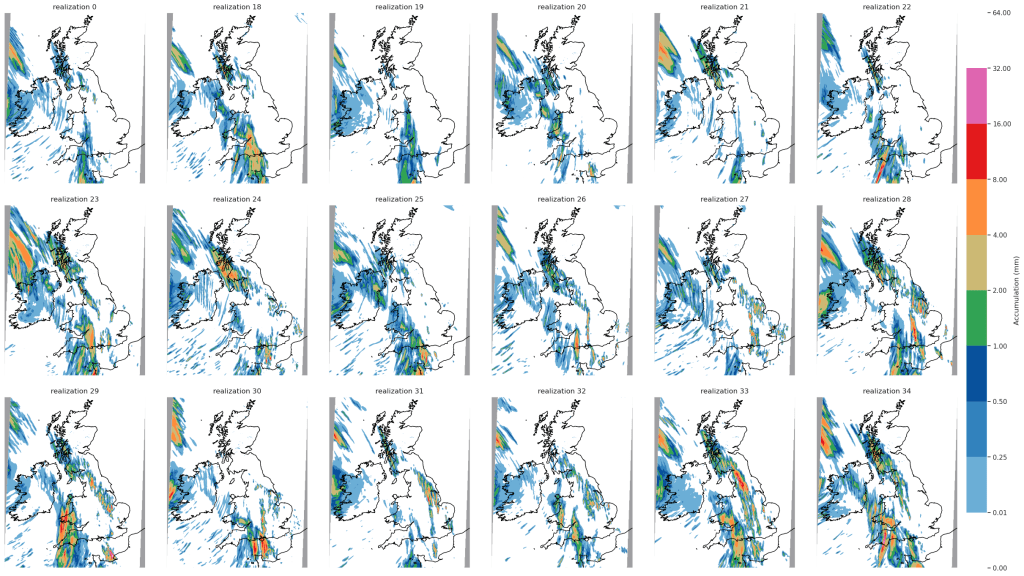

The daily schedule at COP29 was intense. With only one week to make the most of the experience, our days were packed with meetings from 9:00AM – 6:00PM. We started each morning with the RINGO (Research and Independent Non-Governmental Organisations) meeting, which brought together members of the observer scientific community. These sessions provided a valuable space to discuss key themes and points of interest for the day, while also offering great networking opportunities.

The rest of the day was a whirlwind of press conferences, negotiations, and side events hosted by a wide range of organisations. Most events were open to all attendees, though some, particularly negotiations in the second week and high-profile press conferences (such as those featuring Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the UN!), were closed-door.

Another key aspect of our responsibilities was meeting twice daily with our team back at the Walker Institute. These sessions were a great chance to share our findings, report on the atmosphere on the ground, and receive valuable recommendations for upcoming events. More often than not, these check-ins also provided a much-needed energy and mood boost to keep us going through the busy days!

How did we decide on what to attend?

Understanding the true scope of events and talks at COP took a while to get your head around. There is so much going on, and so much you could be going to it always felt like you were missing something. It was helpful to be able to think of the types of events you could go to into three different categories: the negotiations, the side events and the pavilion events. Each one of these had quite a different atmosphere, which was helpful to consider when deciding what to go to.

The pavilions were basically a full conference on their own, with every country and NGO having their own elaborately decorated area. Talks here were slightly more informal and there was a wide diversity of topics. If you wanted to get some information on a more specific topic and also have time to talk with the people presenting this was the place to be.

The side events were often more specific to the ongoing negotiations and included panel discussions and press conferences. These were often really exciting opportunities to get an update on the negotiations that we might not have been allowed to sit in on, and they often provided a more candid and emotive response to the developments.

Lastly were the negotiations themselves. These were very slow and bureaucratic, but despite this, they were really fascinating to watch. It was what was going on in these negotiation rooms that really mattered to the outcome of COP! We had been given very good advice before we went to properly follow just one of the negotiation pieces so that you could understand how it was being shaped over time. However, as we attended the second week, the negotiations occurring behind closed doors increased more and more, and the agenda for these was constantly changing. We found it best to just jump on any opportunity there was to attend one of these as they became increasingly difficult to access.

Having an overview of the different potential experiences in each of these parts of COP made it easier to asses what to go to and what might be interesting at any given time.

Picture 3, 4, and 5 show various events that happened in COP29, including a press conference, a science pavilion event and a plenary.

Who was someone interesting you met?

“While waiting in a queue to get into a negotiation, I met a delegate from an NGO based in South Africa. Through links to local religious groups, she helped guide communities to access climate-related financial aid. We discussed how amendments being made during different negotiations were having a direct impact on the accessibility of these funds. This provided a powerful reminder of how the negotiations had an impact on some of the most vulnerable communities not only in South Africa but all over the world. Having her watching and voicing opinions to negotiators between events provided a channel for these voices to be heard.” – Thea

“Among the many incredible individuals I met, my interaction with two indigenous women from Chile left a profound impact. Their presentation on the consequences of lithium extraction in the Atacama Desert was both heartbreaking and inspiring. They spoke passionately about the devastating effects of privatized water and mineral resources, which have left their communities struggling with water scarcity and ecological exhaustion. Their unwavering determination to fight for their rights and protect their environment, despite significant challenges, was a powerful reminder of the human cost of unsustainable practices. Their story underscored the importance of amplifying marginalized voices in global climate discussions” – Juan

What is the role of the host country and how much influence do they have?

Hosting a COP entails significant responsibilities, including providing the facilities, security, and leadership required to ensure the summit’s success. In many ways, we were impressed by Azerbaijan’s efforts as the COP29 presidency. The facilities were well-prepared, and the transportation system was particularly noteworthy—clear, organised, and highly efficient, running seamlessly throughout the two weeks to help delegates commute to and from the conference centre with ease.

However, Azerbaijan’s selection as host sparked controversy from the moment it was announced at the end of COP28 in Dubai. One of the reasons was this it marked the third consecutive year that a petrostate was appointed to host the climate summit, raising concerns about potential conflicts of interest. This issue became a recurring theme throughout the conference, dominating discussions and even prompting high-profile criticisms. For example, Christiana Figueres, former UN climate chief, wrote an open letter during the first week, asserting that the COP process had become “no longer fit for purpose.”

By the second week, questions about the presidency’s ability to guide negotiations effectively were widespread. As the host country, Azerbaijan was expected to lead efforts to foster consensus among governments and non-Party stakeholders, particularly on critical issues like the NCQG and draft texts. Yet, progress was slow, and negotiations stretched into Saturday, further fuelling doubts about the presidency’s capacity to align its leadership with COP’s overarching goals.

Post-COP

What surprised you the most?

“One of the most exciting and surprising things about COP was how accessible everything felt. As someone who wasn’t there for more than just to communicate what was happening to students at COPCAS, it felt really incredible that we were given access to the negotiations and all the plenary sessions. I obviously knew this was going to be the case before we went, but it was only really sitting when in on these events did I realise how unique of an opportunity this was.” – Thea

“One of the most striking aspects for me of attending last year’s COP was the incredible diversity of attendees, showcasing the universal impact of climate change and the essential need for broad representation in climate discussions. Among the most inspiring aspects was the strong presence of young people and activists, whose energy and commitment highlighted the vital role of the next generation in driving meaningful climate action” – Juan

What do we think of the COP process?

Going to COP and sitting in on the negotiations made the enormity of ambition and geopolitical complexity of bilateral agreements evident. Countries – with vastly different agendas and core beliefs – coming around a table trying to agree on something is an absurdly ambitious arrangement. Reducing fossil fuel consumption is unlike any another problem we face; their presence is pervasive in all of our lives. Fossil fuels are a bedrock of wealth and power in our global political economy. Despite alternative energies booming, and 2024 confirmed as the warmest year on record, this makes fossil fuels hard for the world to walk away from at the speed we need to do so.

Whilst COP can be critiqued for being slow and disappointing, there remains hope in the vision of these bilateral negotiations. Given the increase in conflict and geopolitical instability these past few years, I left COP with an appreciation for the fact that there is still a negotiating table.

However, attending COP also brought to light how important it is to have ambitious domestic policies. COP will never really be the space where radical or big change will happen; this is instead the space where countries are all brought onto the same page. I think we left with more conviction that local politics and policies are where these larger changes need to happen.

Picture 6, Powerful presentation by Enkhuun Byambadorji on Transforming Climate Narratives for Healthy. Picture 7, Organised protests by activists inside the Blue Zone.

Environments

What tips would you give to someone who is hoping to attend next year?

- Apply!! It’s an amazing opportunity both professionally and personally and it shouldn’t be missed.

- Wear comfortable yet formal attire. You will be walking around for most of the day but also meeting important and really cool people, so you definitely still want to look the part.

- Have business cards for networking

- Bring a power bank

- Practice your elevator pitch- in case you stumble across somebody interested in your research.

- Take lots of pictures!

Conclusion

We wanted to end this blog by saying a massive thank you to the Walker Institute for their support in making this experience possible. Attending COP29 was a transformative journey that deepened our commitment to climate action and inspired us to continue advocating for a sustainable future.