By Laura Risley

Ocean data assimilation (DA) is vital. Firstly, it is essential to improving forecasts of ocean variables. Not only that, the interaction between the ocean and atmosphere is key to numerical weather prediction (NWP) as coupled ocean-atmosphere DA schemes are used operationally.

At present, observations of the ocean currents are not assimilated operationally. This is all set to change, as satellites are being proposed to measure these ocean currents directly. Unfortunately, the operational DA systems are not yet equipped to handle these observations due to some of the assumptions made about the velocities. In my work, we propose the use of alternative velocity variables to prepare for these future ocean current measurements. These will reduce the number of assumptions made about the velocities and is expected to improve the NWP forecasts.

What is DA?

DA combines observations and a numerical model to give a best estimate of the state of our system – which we call our analysis. This will lead to a better forecast. To quote my lunchtime seminar ‘Everything is better with DA!’.

Our model state usually comes from a prior estimate which we refer to as the background. A key component of data assimilation is that the errors present in both sets of data are taken into consideration. These uncertainties are represented by covariance matrices.

I am particularly interested in variational data assimilation, which formulates the DA problem into a least squares problem. Within variational data assimilation the analysis is performed with a set of variables that differ from the original model variables, called the control variables. After the analysis is found in this new control space, there is a transformation back to the model space. What is the purpose of this transformation? The control variables are chosen such that they can be assumed approximately uncorrelated, reducing the complexity of the data assimilation problem.

Velocity variables in the ocean

My work is focused on the treatment of the velocities in NEMOVAR. This is the data assimilation software used by the NEMO ocean model, used operationally at the Met Office and ECMWF. In NEMOVAR the velocities are transformed to their unbalanced components, and these are then used as control variables. The unbalanced components of the velocities are highly correlated, therefore contradicting the assumption made about control variables. This would result in suboptimal assimilation of future surface current measurements – therefore we seek alternative velocity control variables.

The alternative velocity control variables we propose for NEMOVAR are unbalanced streamfunction and velocity potential. This would involve transforming the current control variables, the unbalanced velocities, to these alternative variables using Helmholtz Theorem. This splits a velocity field into its nondivergent (streamfunction) and irrotational (velocity potential) parts. These parts have been suggested by Daley (1993) as more suitable control variables than the velocities themselves.

Numerical Implications of alternative variables

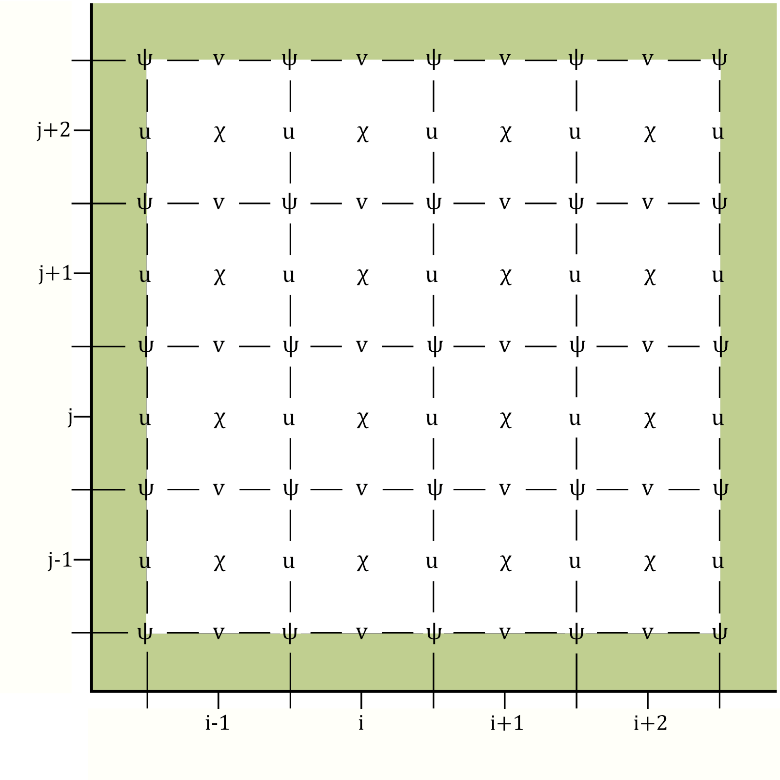

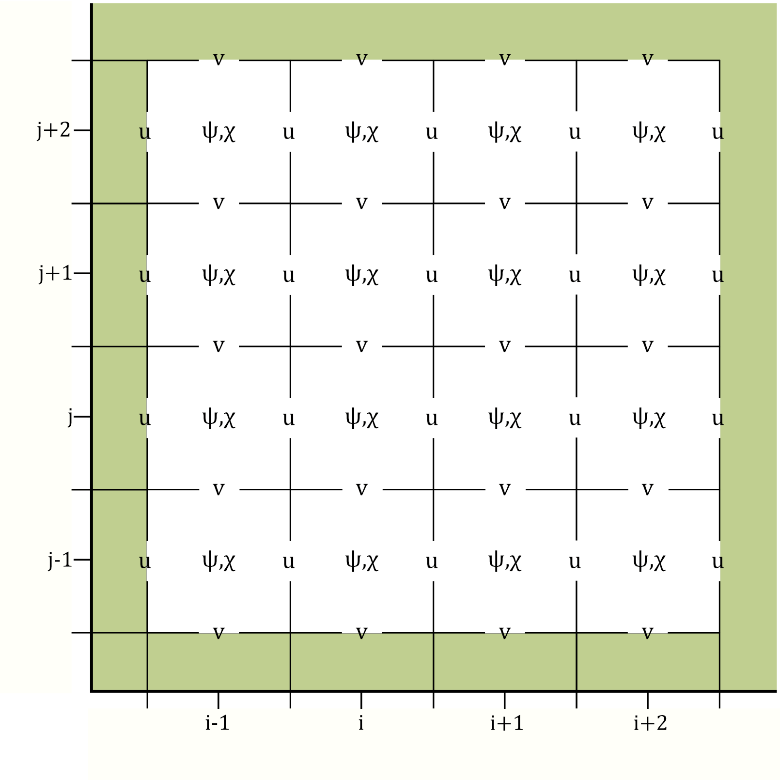

We have performed the transformation to these proposed control variables using the shallow water equations (SWEs) on a 𝛽-plane. To do so we discretised the variables on the Arakawa-C grid. The traditional placement of streamfunction on this grid causes issues with the boundary conditions. Therefore, Li et al. (2006) proposed placing streamfunction in the centre of the grid, as shown in Figure 1. This circumvents the need to impose explicit boundary conditions on streamfunction. However, using this grid configuration leads to numerical issues when transforming from the unbalanced velocities to unbalanced streamfunction and velocity potential. We have analysed these theoretically and here we show some numerical results.

Figure 1: The left figure shows the traditional Arakawa-C configuration (Lynch (1989), Watterson (2001)) whereby streamfunction is in the corner of each grid cell. The right figure shows the Arakawa-C configuration proposed by Li et al. (2006) where streamfunction is in the centre of the grid cell. The green shaded region represents land.

Issue 1: The checkerboard effect

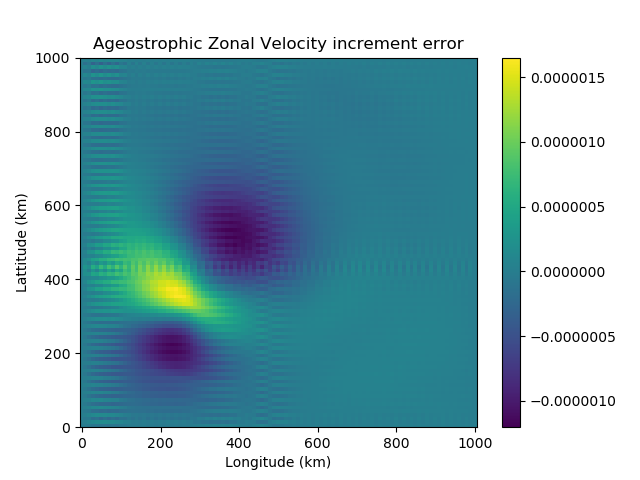

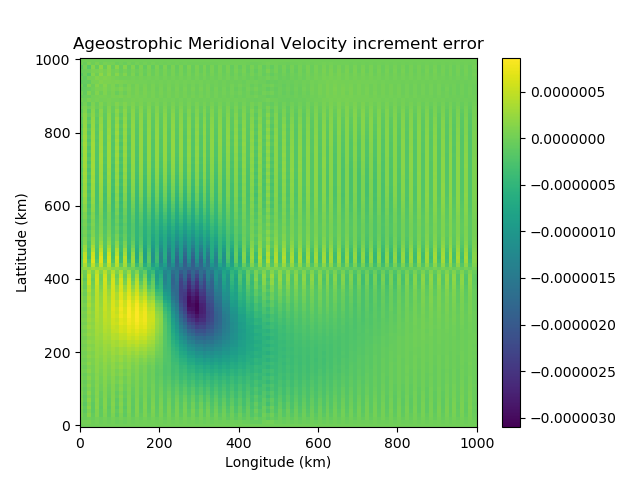

The transformation from the unbalanced velocities to unbalanced streamfunction and velocity potential involves averaging derivatives, due to the location of streamfunction in the grid cell. This process causes a checkerboard effect – whereby we have numerical noise entering the variable fields due to a loss of information. This is clear to see numerically using the SWEs. We use the shallow water model to generate a velocity field. This is transformed to its unbalanced components and then to unbalanced streamfunction and velocity potential. Using Helmholtz Theorem, the unbalanced velocities are reconstructed. Figure 2 shows the checkboard effect clearly in the velocity error.

Figure 2: The difference between the original ageostrophic velocity increments, calculated using the SWEs, and the reconstructed ageostrophic velocity increments. These are reconstructed using Helmholtz Theorem, from the ageostrophic streamfunction and velocity potential increments. On the left we have the zonal velocity increment error and on the right the meridional velocity increment error.

Issue 2: Challenges in satisfying the Helmholtz Theorem

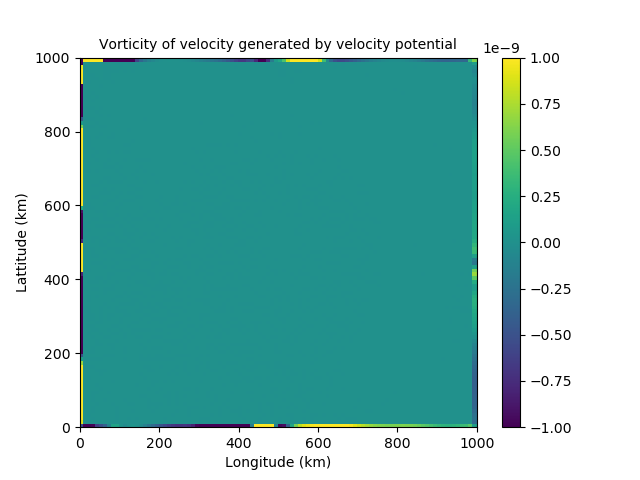

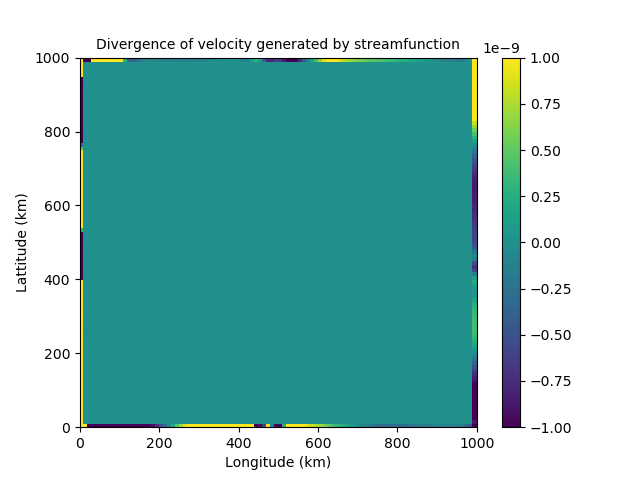

Helmholtz theorem splits the velocity into its nondivergent and irrotational components. We discovered that although streamfunction should be nondivergent and velocity potential should be irrotational, this is not the case at the boundaries, as can be seen in figure 3. This implies the proposed control variables are able to influence each other on the boundary. This would lead to them being strongly coupled and therefore correlated near the boundaries. This directly conflicts the assumption made that our control variables are uncorrelated.

Figure 3: Issues with Helmholtz Theorem near the boundaries. The left shows the divergence of the velocity field generated by streamfunction. The right shows the vorticity of the velocity field generated by velocity potential.

Overall, in my work we propose the use of alternative velocity control variables in NEMOVAR, namely unbalanced streamfunction and velocity potential. The use of these variables however leads to several numerical issues that we have identified and discussed. A paper on this work is in preparation, where we discuss some of the potential solutions. Our next work will further this investigation to a more complex domain and assess our proposed control variables in assimilation experiments.

References:

Daley, R. (1993) Atmospheric data analysis. No. 2. Cambridge university press.

Li, Z., Chao, Y. and McWilliams, J. C. (2006) Computation of the streamfunction and velocity potential for limited and irregular domains. Monthly weather review, 134, 3384–3394.

Lynch, P. (1989) Partitioning the wind in a limited domain. Monthly weather review, 117, 1492–1500.

Watterson, I. (2001) Decomposition of global ocean currents using a simple iterative method. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 18, 691–703

) at each time step in each group, and compare these fields between groups to see if I can find a source of forecast error.

) at each time step in each group, and compare these fields between groups to see if I can find a source of forecast error.

A true revolutionary in the field of theoretical physics and abstract algebra, Amelie Emmy Noether was a German-born inspiration thanks to her perseverance and passion for research. Instead of teaching French and English to schoolgirls, Emmy pursued the study of mathematics at the University of Erlangen. She then taught under a man’s name and without pay because she was a women. During her exploration of the mathematics behind Einstein’s general relativity alongside renowned scientists like Hilbert and Klein, she discovered the fundamentals of conserved quantities such as energy and momentum under symmetric invariance of their respective quantities: time and homogeneity of space. She built the bridge between conservation and symmetry in nature, and although Noether’s Theorem is fundamental to our understanding of nature’s conservation laws, Emmy has received undeservedly small recognition throughout the last century.

A true revolutionary in the field of theoretical physics and abstract algebra, Amelie Emmy Noether was a German-born inspiration thanks to her perseverance and passion for research. Instead of teaching French and English to schoolgirls, Emmy pursued the study of mathematics at the University of Erlangen. She then taught under a man’s name and without pay because she was a women. During her exploration of the mathematics behind Einstein’s general relativity alongside renowned scientists like Hilbert and Klein, she discovered the fundamentals of conserved quantities such as energy and momentum under symmetric invariance of their respective quantities: time and homogeneity of space. She built the bridge between conservation and symmetry in nature, and although Noether’s Theorem is fundamental to our understanding of nature’s conservation laws, Emmy has received undeservedly small recognition throughout the last century. Claudine Hermann is a French physicist and Emeritus Professor at the École Polytechnique in Paris. Her work, on physics of solids (mainly on photo-emission of polarized electrons and near-field optics), led to her becoming the first female professor at this prestigious school. Aside from her work in Physics, Claudine studied and wrote about female scientists’ situation in Europe and the influence of both parents’ works on their daughter’s professional choices. Claudine wishes to give girls “other examples than the unreachable Marie Curie”. She is the founder of the Women and Sciences association and represented it at the European Commission to promote gender equality in Science and to help women accessing scientific knowledge. Claudine is also the president of the European Platform of Women Scientists which represents hundreds of associations and more than 12,000 female scientists.

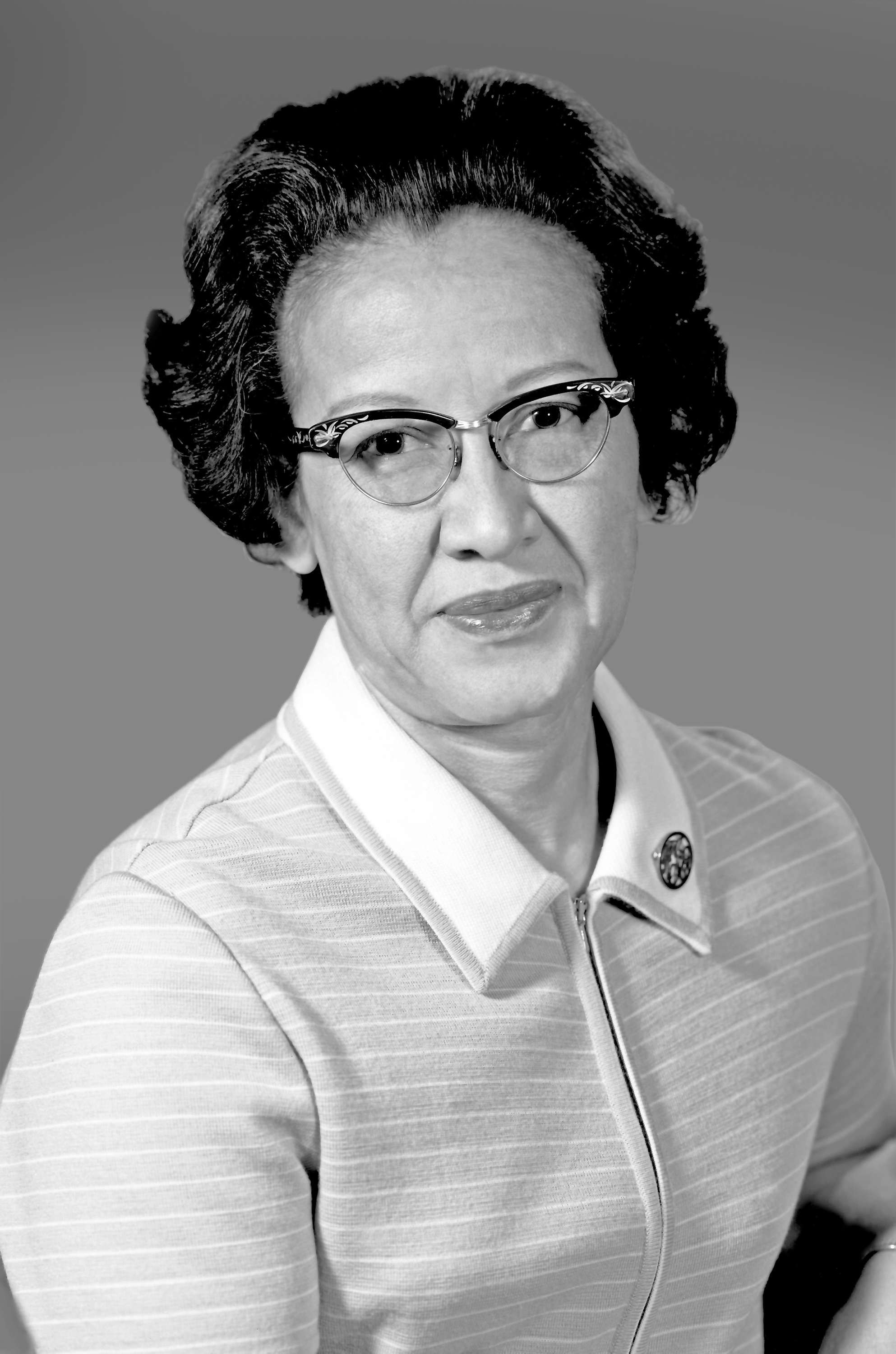

Claudine Hermann is a French physicist and Emeritus Professor at the École Polytechnique in Paris. Her work, on physics of solids (mainly on photo-emission of polarized electrons and near-field optics), led to her becoming the first female professor at this prestigious school. Aside from her work in Physics, Claudine studied and wrote about female scientists’ situation in Europe and the influence of both parents’ works on their daughter’s professional choices. Claudine wishes to give girls “other examples than the unreachable Marie Curie”. She is the founder of the Women and Sciences association and represented it at the European Commission to promote gender equality in Science and to help women accessing scientific knowledge. Claudine is also the president of the European Platform of Women Scientists which represents hundreds of associations and more than 12,000 female scientists. For most people being handpicked to be one of three students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools would probably be the most notable life achievements. However for Katherine Johnson’s this was just the start of a remarkable list of accomplishments. In 1952 Johnson joined the all-black West Area Computing section at NACA (to become NASA in 1958). Acting as a computer, Johnson analysed flight test data, provided maths for engineering lectures and worked on the trajectory for America’s first human space flight.

For most people being handpicked to be one of three students to integrate West Virginia’s graduate schools would probably be the most notable life achievements. However for Katherine Johnson’s this was just the start of a remarkable list of accomplishments. In 1952 Johnson joined the all-black West Area Computing section at NACA (to become NASA in 1958). Acting as a computer, Johnson analysed flight test data, provided maths for engineering lectures and worked on the trajectory for America’s first human space flight.

Women however were not allowed on such ships, thus Marie Tharp was stationed in the lab, checking and plotting the data. Her drawings showed the presence of the North Atlantic Ridge, with a deep V-shaped notch that ran the length of the mountain range, indicating the presence of a rift valley, where magma emerges to form new crust. At this time the theory of plate tectonics was seen as ridiculous. Her supervisor initially dismissed her results as ‘girl talk’ and forced her to redo them. The same results were found. Her work led to the acceptance of the theory of plate tectonics and continental drift.

Women however were not allowed on such ships, thus Marie Tharp was stationed in the lab, checking and plotting the data. Her drawings showed the presence of the North Atlantic Ridge, with a deep V-shaped notch that ran the length of the mountain range, indicating the presence of a rift valley, where magma emerges to form new crust. At this time the theory of plate tectonics was seen as ridiculous. Her supervisor initially dismissed her results as ‘girl talk’ and forced her to redo them. The same results were found. Her work led to the acceptance of the theory of plate tectonics and continental drift. Ada Lovelace was a 19th century Mathematician popularly referred to as the “first computer programmer”. She was the translator of “Sketch of the Analytical Engine, with Notes from the Translator”, (said “notes” tripling the length of the document and comprising its most striking insights) one of the documents critical to the development of modern computer programming. She was one of the few people to understand and even fewer who were able to develop for the machine. That she had such incredible insight into a machine which didn’t even exist yet, but which would go on to become so ubiquitous is amazing!

Ada Lovelace was a 19th century Mathematician popularly referred to as the “first computer programmer”. She was the translator of “Sketch of the Analytical Engine, with Notes from the Translator”, (said “notes” tripling the length of the document and comprising its most striking insights) one of the documents critical to the development of modern computer programming. She was one of the few people to understand and even fewer who were able to develop for the machine. That she had such incredible insight into a machine which didn’t even exist yet, but which would go on to become so ubiquitous is amazing!

Over the past months, researchers in the

Over the past months, researchers in the