Climate scientists have a lot of insight into the factors driving weather systems in the mid-latitudes, where the rotation of the earth is an important influence. The tropics are less well served, and this can be a problem for global climate models which don’t capture many of the phenomena observed in the tropics that well.

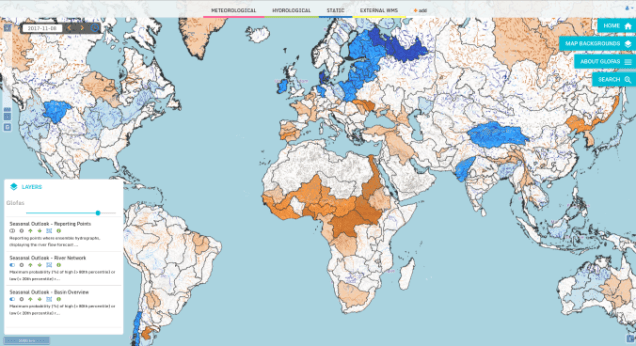

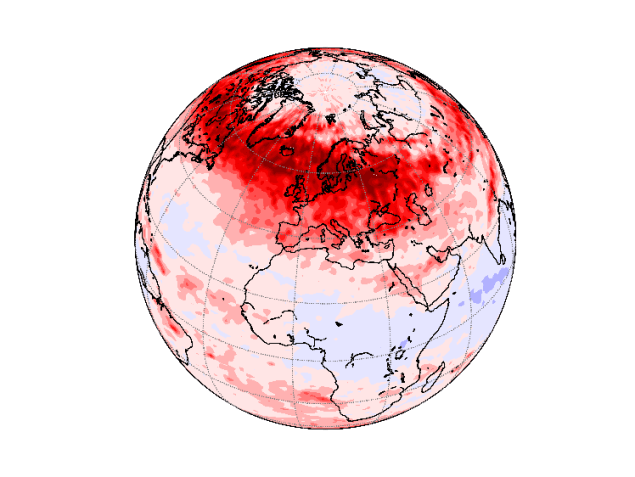

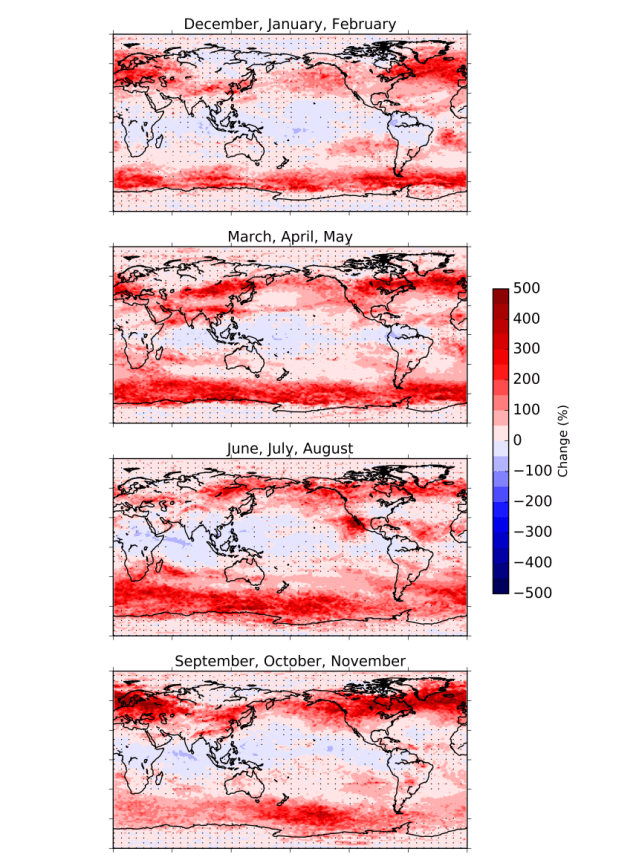

What we do know about the tropics however is that despite significant contrasts in sea surface temperatures (Fig. 1) there is very little horizontal temperature variation in the atmosphere (Fig. 2) – because the Coriolis force (due to the Earth’s rotation) that enables this gradient in more temperate climates is not present. We believe that the large-scale circulation acts to minimise the effect these surface contrasts have higher up. This suggests a model for vertical wind which cools the air over warmer surfaces and warms it where the surface is cool, called the Weak Temperature Gradient (WTG) Approximation, that is frequently used in studying the climate in the tropics.

Thermodynamic ideas have been around for some 200 years. Carnot, a Frenchman worried about Britain’s industrial might underpinning its military potential(!), studied the efficiency of heat engines and showed that the maximum mechanical work generated by an engine is determined by the ratio of the temperatures at which energy enters and leaves the system. It is possible to treat climate systems as heat engines – for example Kerry Emanuel has used Carnot’s idea to estimate the pressure in the eye of a hurricane. I have been building on a recent development of these ideas by Olivier Pauluis at New York University who shows how to divide up the maximum work output of a climate heat engine into the generation of wind, the lifting of moisture and a lost component, which he calls the Gibbs penalty, which is the energetic cost of keeping the atmosphere moist. Typically, 50% of the maximum work output is gobbled up by the Gibbs penalty, 30% is the moisture lifting term and only 20% is used to generate wind.

For my PhD, I have been applying Pauluis’ ideas to a modelled system consisting of two connected tropical regions (one over a cooler surface than the other), which are connected by a circulation given by the weak temperature gradient approximation. I look at how this circulation affects the components of work done by the system. Overall there is no impact – in other words the WTG does not distort the thermodynamics of the underlying system – which is reassuring for those who use it. What is perhaps more interesting however, is that even though the WTG circulation is very weak compared to the winds that we observe in the two columns, it does as much work as is done by the cooler column – in other words its thermodynamic importance is huge. This suggests that further avenues of study may help us better express what drives the climate in the tropics.

Over the past months, researchers in the

Over the past months, researchers in the

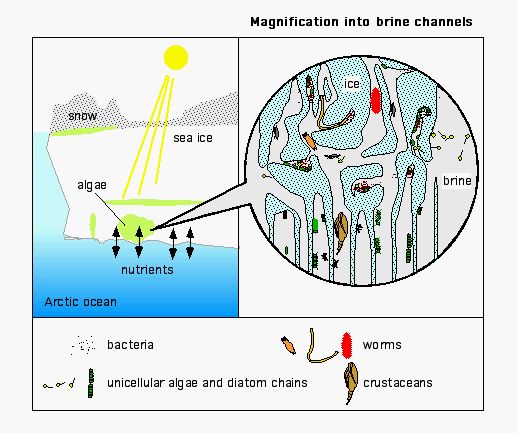

Schematic showing some dynamic features of sea ice 3.

Schematic showing some dynamic features of sea ice 3.