Isabel Smith – i.h.smith@pgr.reading.ac.uk

Hannah Croad – h.croad@pgr.reading.ac.uk

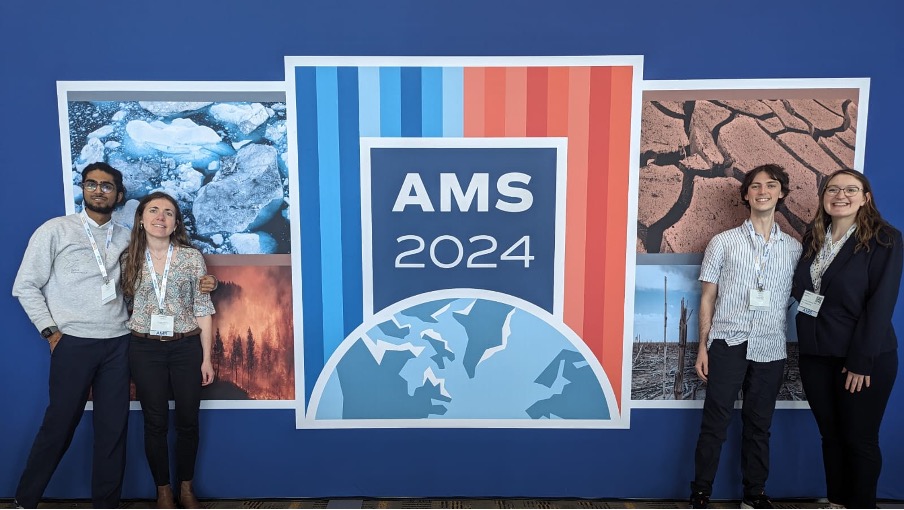

In January 2024, Isabel Smith and Hannah Croad attended the 104th American Meteorological Society (AMS) annual meeting in Baltimore, Maryland. As fourth-year PhD students this was something of a “last hurrah” of our PhDs (with the remainder of our project monies and carbon budgets being used up), representing a fantastic opportunity to see the latest research happening in meteorology, meet other scientists working in our respective fields, and present our own work to a large audience at this late stage in our projects.

We arrived in Baltimore on the Friday before the conference started, navigating the busy streets near the Inner Harbour in a thick fog to find our hotel. The many plumes of steam coming from vents in the street were somewhat disconcerting, but it turns out this is the result of an underground steam pipe system and is completely safe. As exciting as this was, Baltimore is slightly lacking in terms of other tourist attractions, so on the Saturday we chose to visit Washington DC, only a 1-hour train ride away. We had a great day wandering about the capital city, visiting the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum, and seeing all the iconic monuments including the Capitol building and the White House. Back in Baltimore on the Sunday, there was a buzz about the city as Baltimore’s NFL Ravens team were hosting the Kansas City Chiefs. Although we did not attend the game, and the Ravens lost, it was a great honour to be within a mile radius of Taylor Swift.

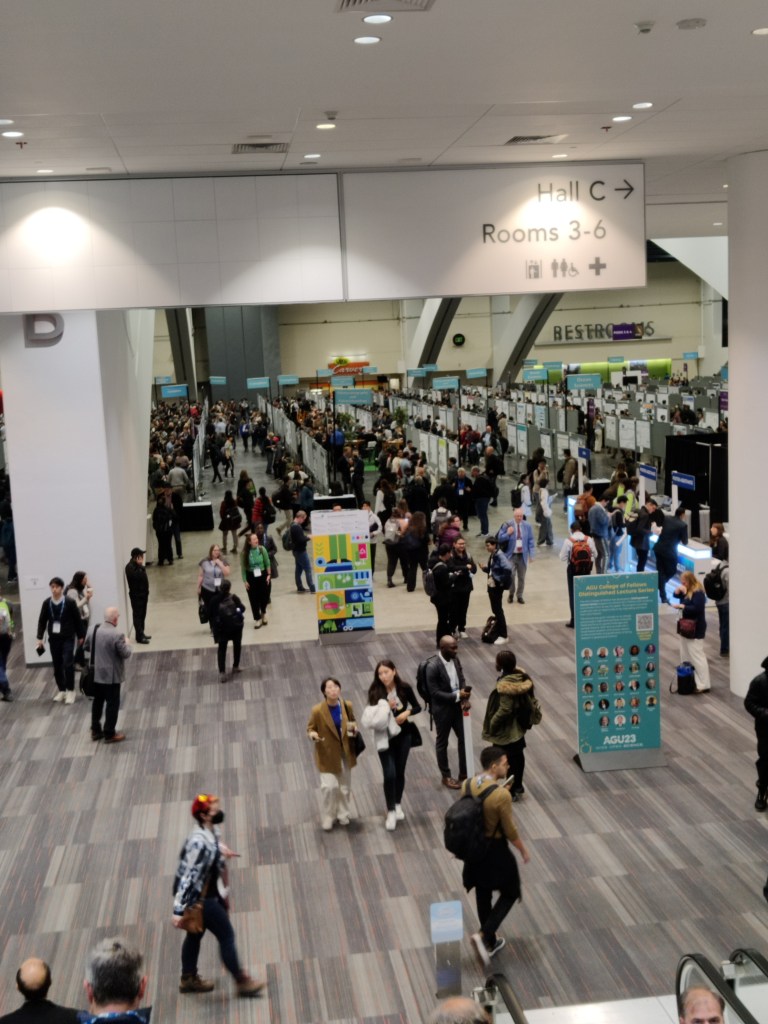

The conference started on Sunday, with registration (where we picked up some cool lanyards), speeches from outgoing and incoming AMS presidents, student posters, and an interesting panel discussion about how the two sides of American politics must come together in the fight against climate change. It was also great to meet up with two first-year PhD students from the department, Karan Ruparell and Robby Marks, for who this was the first international conference of their PhD.

The main conference programme was scheduled from Monday to Thursday. The size of the conference was overwhelming, with up to 40 parallel sessions at any one time amongst the many different mini- conferences and symposia. Hence, it was important to research which sessions you wanted to go to in advance. We did this using the AMS app, although it was rather slow and buggy (AMS if you’re reading this, please improve for next year). Isabel attended the 4-day symposium on Aviation, Range and Aerospace meteorology (ARAM), being held in the same room of the conference center each day. In contrast, Hannah attended many different sessions and so was continuously moving between different rooms, with the highlights being the Daniel Keyser symposium on synoptic-dynamic meteorology on Monday and the Polar symposium on Thursday.

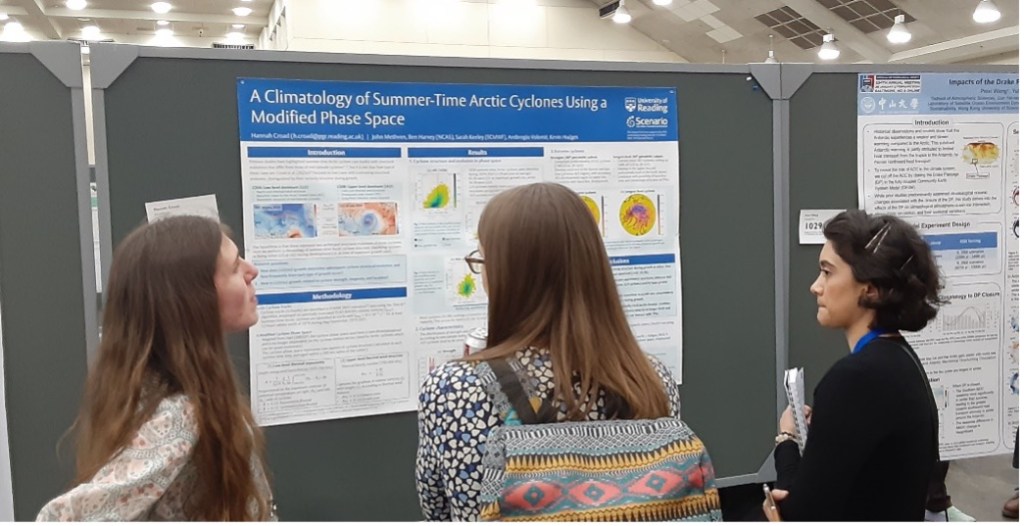

The biggest day of the conference for us was Thursday, as we were both going to be presenting our work. Starting bright and early, Isabel gave an oral presentation in the ARAM symposium, talking about her work on trends in aviation scale turbulence. In the afternoon, Hannah presented a poster in the Polar symposium, talking about her climatology of summer-time Arctic cyclones. We found it interesting to compare the two different presentation formats. For oral presentations your research is likely to reach more people as you have a captive audience for 12 minutes, but the format is more nerve-wracking and there is only limited time for questions and discussion. Less people are likely to visit a poster, but the 1.5 hour format allows for longer and more in-depth discussion with those who do approach you (assuming your poster survives the flight in your suitcase of course). Regardless of the format, we both really enjoyed sharing and discussing our work with other scientists and found the day to be thoroughly rewarding.

In summary, we both had a fantastic time at the AMS 2024 annual meeting. Not only did we enjoy and learn a lot from the conference talks and posters, it was also great to catch up with current and ex-students from the department, old friends and lecturers from our time at the University of Oklahoma as undergraduate students, and to make new contacts in our respective fields. Although large conferences like AMS can be daunting, attending gives you an appreciation of the wide variety of research happening all over the world, conducive to a stimulating and inspiring atmosphere. They also provide fantastic opportunities to network and to learn new things outside of your immediate research topic. Hence, we would both recommend attending a big conference like AMS if you get the chance to do so in your PhD!

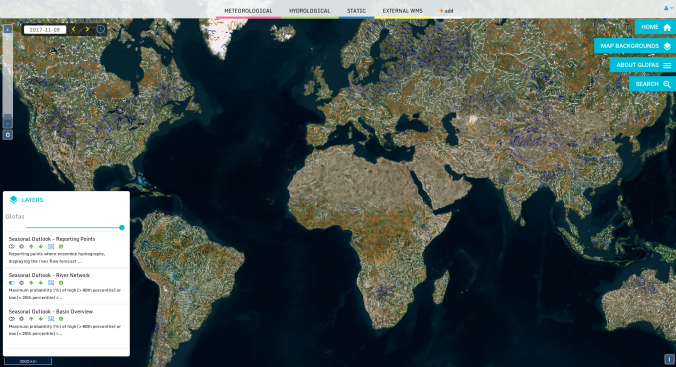

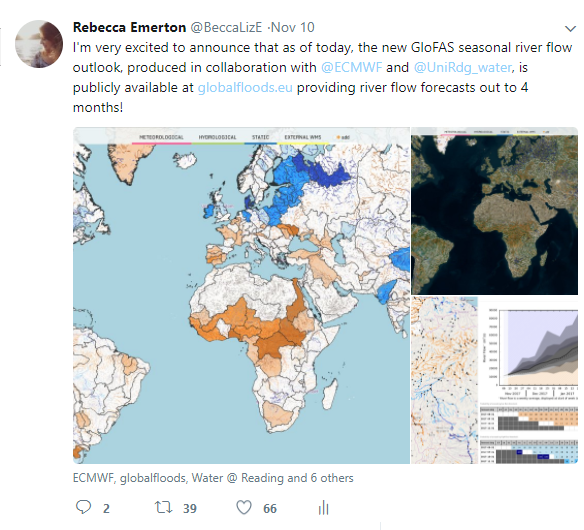

Over the past months, researchers in the

Over the past months, researchers in the