Email: js102@zepler.net Web: datumedge.co.uk Twitter: @hertzsprrrung

This article was originally posted on the author’s personal blog.

If we know which way the wind is blowing then we can predict a lot about the weather. We can easily observe the wind moving clouds across the sky, but the wind also moves air pollution and greenhouse gases. This process is called transport or advection. Accurately simulating the advection process is important for forecasting the weather and predicting climate change.

I am interested in simulating the advection process on computers by dividing the world into boxes and calculating the same equation in every box. There are many existing advection methods but many rely on these boxes having the correct shape and size, otherwise these existing methods can produce inaccurate simulations.

During my PhD, I’ve been developing a new advection method that produces accurate simulations regardless of cell shape or size. In this post I’ll explain how advection works and how we can simulate advection on computers. But, before I do, let’s talk about how we observe the weather from the ground.

In meteorology, we generally have an incomplete picture of the weather. For example, a weather station measures the local air temperature, but there are only a few hundred such stations dotted around the UK. The temperature at another location can be approximated by looking at the temperatures reported by nearby stations. In fact, we can approximate the temperature at any location by reconstructing a continuous temperature field using the weather station measurements.

The advection equation

So far we have only talked about temperatures varying geographically, but temperatures also vary over time. One reason that temperatures change over time is because the wind is blowing. For example, a wind blowing from the north transports, or advects, cold air from the arctic southwards over the UK. How fast the temperature changes depends on the wind speed, and the size of the temperature contrast between the arctic air and the air further south. We can write this as an equation. Let’s call the wind speed and assume that the wind speed and direction are always the same everywhere. We’ll label the temperature

, label time

, and label the south-to-north direction

, then we can write down the advection equation using partial derivative notation,

This equation tells us that the local temperature will vary over time (), depending on the north-south temperature contrast (

) multiplied by the wind speed

.

Solving the advection equation

One way to solve the advection equation on a computer is to divide the world into boxes, called cells. The complete arrangement of cells is called a mesh. At a point at the centre of each cell we store meteorological information such as temperature, water vapour content or pollutant concentration. At the cell faces where two cells touch we store the wind speed and direction. The arrangement looks like this:

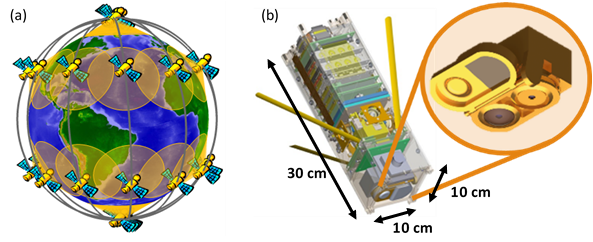

The above example of a mesh over the UK uses cube-shaped cells stacked in columns above the Earth, and arranged along latitude and longitude lines. But more recently, weather forecasting models are using different types of mesh. These models tesselate the globe with squares, hexagons or triangles.

Weather models must also rearrange cells in order to represent mountains, valleys, cliffs and other terrain. Once again, different models rearrange cells differently. One method, called the terrain-following method, shifts cells up or down to accommodate the terrain. Another method, called the cut-cell method, cuts cells where they intersect the terrain. Here’s what these methods look like when we use them to represent an idealised, wave-shaped mountain:

Once we’ve chosen a mesh and stored temperature at cell centres and the wind at cell faces, we can start calculating a solution to the advection equation which enables us to forecast how the temperature will vary over time. We can solve the advection equation for every cell separately by discretising the advection equation. Let’s consider a cell with a north face and a south face. We want to know how the temperature stored at the cell centre, , will vary over time. We can calculate this by reconstructing a continuous temperature field and using this to approximate temperature values at the north and south faces of the cell,

and

,

where is the distance between the north and south cell faces. This is the same reconstruction process that we described earlier, only, instead of approximating temperatures using nearby weather station measurements, we are approximating temperatures using nearby cell centre values.

There are many existing numerical methods for solving the advection equation but many do not cope well when meshes are distorted, such as terrain-following meshes, or when cells have very different sizes, such as those cells in cut-cell meshes. Inaccurate solutions to the advection equation lead to inaccuracies in the weather forecast. In extreme cases, very poor solutions can cause the model software to crash, and this is known as a numerical instability.

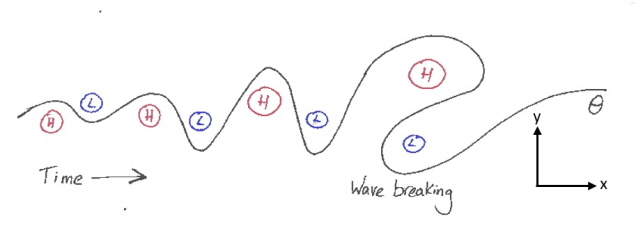

We can see a numerical instability growing in this idealised example. A blob is being advected from left to right over a range of steep, wave-shaped mountains. This example is using a simple advection method which cannot cope with the distorted cells in this mesh.

We’ve developed a new method for solving the advection equation with almost any type of mesh using cubes or hexagons, terrain-following or cut-cell methods. The advection method works by reconstructing a continuous field from data stored at cell centre points. A separate reconstruction is made for every face of every cell in the mesh using about twelve nearby cell centre values. Given that weather forecast models have millions of cells, this sounds like an awful lot of calculations. But it turns out that we can make most of these calculations just once, store them, and reuse them for all our simulations.

Here’s the same idealised simulation using our new advection method. The results are numerically stable and accurate.

Further reading

A preprint of our journal article documenting the new advection method is available on ArXiv. I also have another blog post that talks about how to make the method even more accurate. Or follow me on Twitter for more animations of the numerical methods I’m developing.